| wilderness |

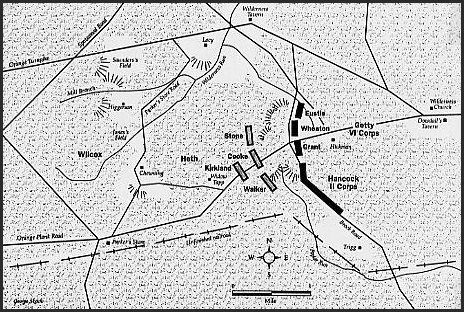

The Wilderness: Ghosts in the Darknessby Nicholas E. Hollis Summary In Spring 1864, Lee ordered Longstreet to re-deploy from East Tennessee to central Virginia to guard Richmond against the anticipated Union campaign under Grant. Longstreet’s 1st Corps was strategically posted at Gordonsville (28 miles southwest of Wilderness), enabling him to protect against invasion via the Shenandoah Valley, or quickly reunite with the main body of Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia, should the thrust come near Fredericksburg. Early on May 4, Lee realized Grant was rushing directly, crossing the Rapidan, and summoned Longstreet. “Old Pete” received the orders to march at 1:00 p.m. that day, and his columns broke camp and began a forced march toward Wilderness at 4:00 p.m. (three hours later). Vastly outnumbered with only Ewell’s and Hill’s corps at hand on May 5, Lee sought to delay Grant’s drive, containing him in the dense woods long enough for Longstreet’s corps to move up on the right where offensive actions against the Union Army might be possible. But intense fighting in the late afternoon/early evening of May 5, starting with attacks by Warren’s V corps and Sedgwick’s VI corps, left the Hill/Ewell line wavering with Union Commander Hancock’s Corps II threatening Lee’s right (Hill) near Widow Tapp Farm along the Brock Road.

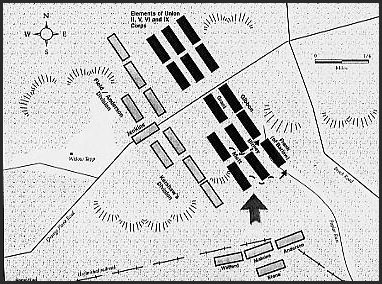

A Timely Intervention Lee had ridden to the front, trying to rally Hill’s retreating men, when the Texans under Kershaw (Hood’s old brigade) moved up and shouted: “Lee, to the rear!” followed by a refusal of the men to go forward until their beloved leader took himself out of danger. By 8:00 a.m., Longstreet had checked Hancock’s advance and began pushing back his right flank, while pummeling Wadsworth’s Federals on the left. In “the fog of the battle,” with confusion and mistakes piling up, the Army of the Potomac suddenly seemed lethargic – and momentum shifted to “Old Pete.” Wisely, Longstreet had held three brigades out of the heavy fighting as reserves – and, receiving information on the existence of unfinished railroad trace extending through the woods along the battlefield’s right (southern edge), ordered his fresh troops to move concealed under the dense cover along the twelve-foot-wide gap and form an attack line on Hancock’s left. When the famous flank attack began at 11:00 a.m., with rebel yells magnifying their numbers as they came crashing through the woods, the Federals could hardly see them.

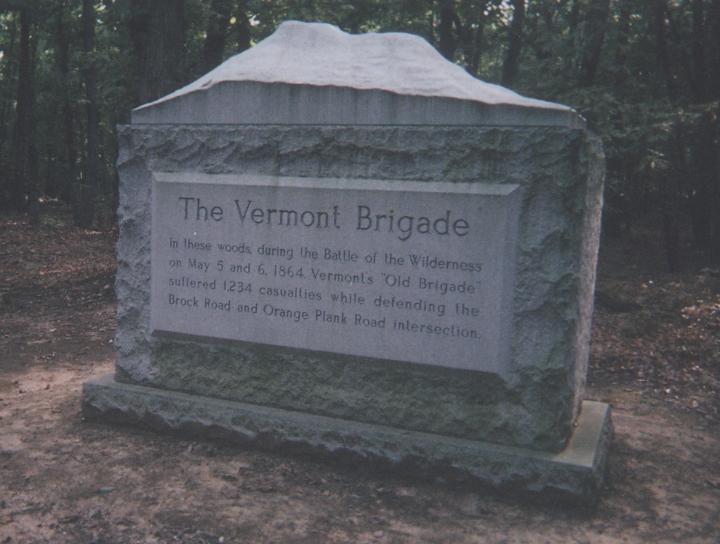

Many fired blindly into the woods. Errant federal artillery fire raked Vermonters under Brigadier General Lewis A. Grant from their rear, making the terrifying situation worse. The men of the 3rd and 4th Vermont regiments in the first line, absorbed the brunt of the Confederate fire exploding from the woods, and were reinforced with the 2nd Vermont and the 6th Vermont. The Green Mountain brigades hung tough, under a hail of bullets, exacting ghastly casualties. The sons of Vermont were stubborn that morning. Amidst the low-hanging smoke and fires, with most of their Federal comrades in rout, the Vermonters held the intersection of Brock and Orange Plank roads. Heavy Hand of

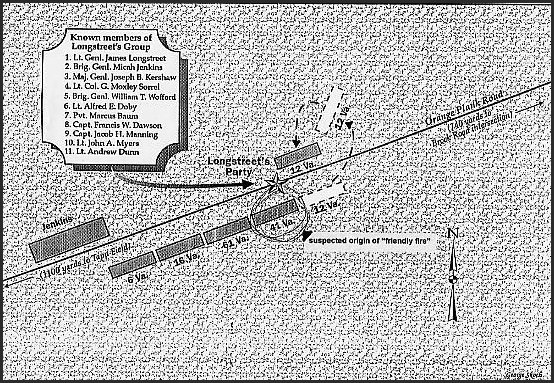

Fate: Longstreet’s Wounding

A hush fell on the advancing rebels. The counterattack stalled. Lee intervened and, after using precious time to realign his troops, ordered a frontal assault on Hancock’s center – reminiscent of Pickett’s charge at Gettysburg – with similar results. The Union center held without great difficulty with rebels taking staggering losses. Exhaustion descended. The troops dug new earthworks, while listening to the screams of the wounded being consumed by fires in the underbrush of “No Man’s Land.” Conclusion On the evening of May 6th, Lt. General U.S. Grant whittled sticks and chided some of his lieutenants: “I am heartily tired of hearing about what Lee is going to do. Some of you always seem to think he is suddenly going to turn a double somersault and land in our rear and on both of our flanks at the same time. Go back to your commands, and try to think about what we are going to do instead of wondering what Lee is going to do.” Grant had decided his next move: a march off Lee’s flank toward Spotsylvania Courthouse and Richmond, and he could take this bold action because of Vermont valor in holding the key road/intersections. The orders were issued the following morning (May 7). The Union troops cheered when they realized Grant would not retreat. Perhaps somehow this justified horrors of the Wilderness. But as one of the epic battles of the Civil War, much of what happened at Wilderness remains a mystery, blurred in the swirl of unspeakable terrors and events which followed. Longstreet, borne off on a litter after designating R.H. Anderson to take his command, had the presence of mind and courage to raise his hat off his face – thereby reassuring his troops that their leader would fight another day. Longstreet was moved to safety at a private home in Lynchburg, Virginia and later, further south near Augusta, Georgia. The mini-ball had passed through his neck and shattered his brachial plexus – an injury which cost him the use of his right arm. It was a slow recovery, but “Old Pete” rejoined Lee later in October 1864, and was placed in charge of Richmond’s defenses. Longstreet stayed by Lee’s side until Appomattox.

Call to Action

Suggested References Benedict, G.G. Vermont in the Civil War: A History of the Part Taken by Vermont Soldiers and Sailors in the War for the Union, 1861-1865 (2 Volumes). Burlington, VT: Free Press Association, 1897 (Volume 1, p. 235). Grant, Gen. L.A. “In the Wilderness.” Washington, DC: National Tribune (January 28, 1897). Hollis, N.E. "Small Victories at Wilderness Battlefield" (Editorial). Culpeper Star-Exponent (October 21, 2009); and "Out of the Wilderness: Heroes on Both Sides are Easier to Locate" (Op.Ed). Fredericksburg Free Lance-Star (November 8, 2009). Hollis, N.E. Commentary: "Is Sacred Ground Walmart's Manifest Destiny." Fredericksburg Free Lance-Star (March 13, 2010). Longstreet, James A. From Manassas to Appomattox: Memoirs of the Civil War in America. New York: Da Capo Press Edition, 1992 (pp. 551-571). Reardon, Carol. The Other Grant: Lewis A. Grant and the Vermont Brigade (article published in The Wilderness Campaign). University of North Carolina Press: 1997, pp. 201-235. Enlist in the campaign to restore Longstreet's honor!

|

||||||||||||||