|

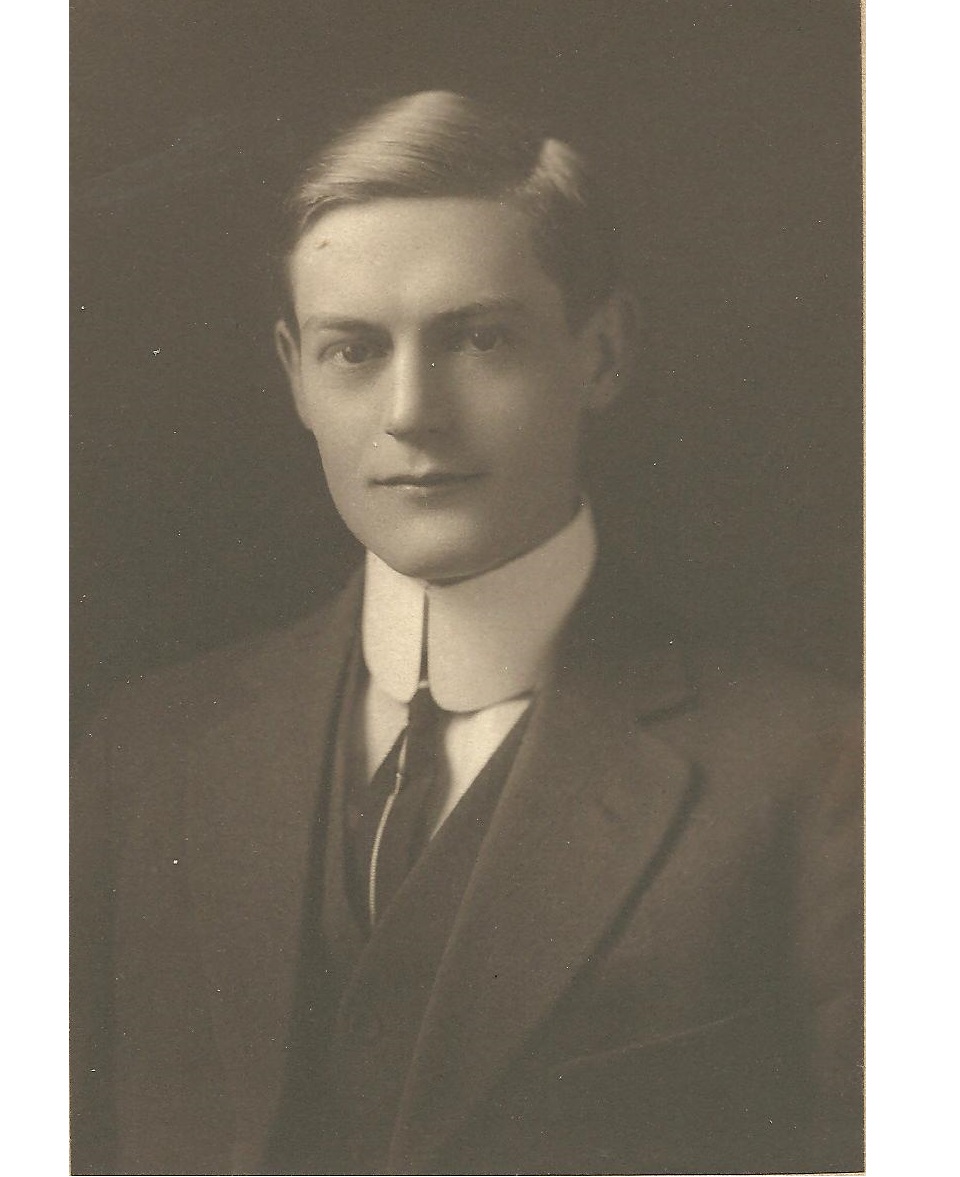

Francis Bates Jennings, M.D. was born on December 4, 1885 in Avondale, New Jersey, the fourth child of William Nevinson Jennings and Susan Geraldine Williams Jennings. His father was a successful, thirty-eight year old entrepreneur-businessman with a growing publishing and engraving company in lower Manhattan. Susan was a self-taught Irish emigrant dedicated to home-making and education. Frank was home-schooled in his early years, being of fragile health, later attending public schools in New Brunswick, New Jersey and Brooklyn, New York near Prospect Park (Boys High). From an early age Frank distinguished himself with natural athleticism, leadership qualities, and dashing good looks. He excelled in football, baseball and rugby – and enjoyed camping, boating and other outdoor pursuits -- benefiting from explorations of the Delaware Valley made possible from his family’s summer retreat near Port Jervis, New York.

Early Tragedies Shape a Life

Frank’s love of outdoor life and early self-reliance developed from watching his older brothers (John E. “Jack” and William ”Bill” Nevinson Jr.) and listening to Jennings family lore through his father’s stories of ancestors dating back to the seventeenth century, and leading up to his grandfather (Joel Albert Jennings). This grandfather was the first family member to graduate from college and Harvard Law School, but became a gold prospector and transcendental lecturer during the 1849 California gold rush. Frank did not know this grandfather who lived a nomadic life, dying of malaria in Panama in 1873, but sensed he had the spirit of a pioneer-adventurer in his genes.

Frank was also a survivor. In the late 1880s, he witnessed helplessly as his three sisters -- Susan Geraldine (5), Adelaide (4), and Dorothea (2) -- succumbed in rapid succession to whooping cough outbreaks. A short time later, while skating on the frozen Passaic River near his family home at night, Frank suddenly fell through a hole in the ice. Immersed in frigid, swift-moving waters, he momentarily lost his bearings and drifted under the ice into the inky, freezing darkness. Quickly regaining his cool-headed composure, Frank remembered there was an air pocket between ice and moving water. He managed to arch his body into a back-float position and, while anchoring his skate-tips into the ice above, gulped needed oxygen. Frank knew he had only a few minutes before hyperthermia would begin paralyzing him -- yet maneuvered calmly, inching his way steadily with gloved hands and skate-tips, in the direction where he thought the ice hole was located. Miraculously, he found it – and, after removing one skate for a pick, pulled himself out of that icy river. Later, warmed by a pot-bellied stove, Frank downplayed the incident, remembering his mother’s traumatic loss of her own little brother (John Lewis Williams), as she watched helplessly, unable to swim, when he drowned in the Neversink River near Post Jervis years earlier.

Although tempered in tragedy, the William Nevinson Jennings family celebrated the birth of a fourth daughter, Ruth Hastings Jennings, in 1893.

During his residency at Brooklyn Hospital, Frank became interested in Nellie Armstrong, a young nurse seven years his junior, who had emigrated from Nova Scotia and was popular with the patients. Nellie came from a big family with a successful father, Edward Lawson Armstrong (1853-1925), who was Superintendent of Schools in Pictou, Nova Scotia. The Armstrong family traced back to Scotland, as a feared warrior clan, but Nellie’s Canadian forbearers had become famous shipbuilders. She was proud of her heritage. After a three-year courtship, the couple was married in Pictou on June 21, 1916.

Yale Mobile Field Hospital in France

Married life for Frank and Nellie came to an abrupt hiatus in April 1917 with the U.S. decision to enter World War I and the formation of the American Expeditionary Force (AEF). When word reached him that a beloved Yale professor and surgeon (Dr. Joseph Marshall Flint) was organizing a special mobile medical unit for field hospital work in France, Frank jumped at the chance and enlisted in the U.S. Army Medical Corps.

He received an officer’s commission as a lieutenant and sailed with the Yale Mobile Medical Unit #39 in August 1917. While the AEF developed and gained strength with minimal action, Unit #39 was stationed near a railhead in Limoges, a beautiful city on the Vienne River in south/central France about one hundred miles northeast of Bordeaux. Six months later, the unit was redeployed to Chaillons near the AEF main concentration at St. Mihiel (General Pershing’s HQ) in the Meuse-Argonne region. The Yale unit served in support of the decisive offensive in October-November 1918 where the AEF, in coordination with Allied forces in the north near Sedan, forged a series of bloody victories, breaking through German lines and morale, leading to the Armistice of November 11.

Challenges of Civilian Life

When Frank Jennings returned to New York a seasoned field surgeon in April 1919, Nellie presented him with the first of three daughters, Geraldine, born a year earlier (1918) while he was in France. He had expected to rejoin the staff of the Brooklyn Hospital where his brother Jack was now a leading surgeon, but inexplicably, instead, had an angry falling out with his superiors, including his brother, over some procedure he considered outdated. He relocated his family to Bristol, Connecticut (outside Hartford) with help from a Yale classmate and began a new practice. Perhaps he hoped for a return to Brooklyn, or quite likely he wanted a fresh start outside his brother’s “sphere of family influence.”

Vision of the Small Modern Hospital

Following the birth of his second daughter, Marion, in November 1919, in Brooklyn, Frank Jennings became an important medical leader in Bristol. For the next eight years, he advanced professionally, becoming a community leader and helping to enlarge the town’s main hospital. He was a gifted surgeon and a voracious reader of medical journals, always seeking greater breadth of knowledge in the rapidly changing medical field. On October 17, 1925, Frank Jennings presented a paper,“The Small Modern Hospital,” before the Hartford County Medical Association annual meeting at Hartford. His talk was a well-prepared argument for small hospitals and caught considerable attention.

Tragic Losses Alter Lives

Professional success was eclipsed, however, with the birth on June 29, 1924 of a blond, blue-eyed son named for Francis Bates Jennings and nicknamed “Bunny.” Having a male heir for continuance of his family branch and his legacy was important to Frank, who traced his lineage to Stephen Jennings of Hatfield and the Great Rescue Mission of 1677-78. With a doting mother and two attentive sisters, young Bunny was the apple of his father’s eye. The healthy toddler was on the flowering edge of infancy, just learning to talk, when he was stricken with the deadly scarlet fever. Once again, Frank – now even as a physician, could do little but watch the disease take its course in his quarantined house. The struggle wore on for three months, and the end came only a few weeks short of Bunny’s third birthday on March 20, 1927 plunging the family into a spiral of deep despair and grief.

Frank Jennings completed his son’s death certificate with a shaking hand, and the family took a sad journey to Brooklyn where his namesaked son was buried in the family plot on a promontory in Evergreen Cemetery. Dr. Jennings resolved never to mention Bunny’s name in family conversation again. The pain was too deep.

After the intense sorrow of his own childhood losses and the shock of the field hospital in France, with modern warfare and gas chemical attacks destroying young men by the thousands, compounded by the unexpected death of his mother, Susan Geraldine, shortly after his return in 1919, the stern warrior-surgeon stood unmanned in the presence of death. His wife, Nellie, suffered a mild nervous breakdown and in the gloomy months that followed, despair turned into depression and his practice suffered. In 1928, matters worsened when a child-patient under Jennings’ care died and the father, a prominent Bristol business leader, became convinced that the physician was to blame. The two men argued and the exchange turned heated. A power struggle ensued and the distraught businessman pulled in his markers vowing Jennings would not practice medicine again in the town. Jennings was forced to leave Bristol under a cloud despite the fact that no formal proceedings were ever initiated.

A String of Misfortunes

Relying on an offer from a Yale classmate, Jennings relocated to York, Pennsylvania with the understanding he would take over the practice of that classmate who wanted to move West. But misfortune played havoc again as Jennings found his colleague’s medical equipment unusable and the practice virtually non-existent. Months after hanging out his shingle with no patients appearing, Jennings discovered his colleague (long gone to Oregon) had actually used the place to conduct illegal abortions. As a result, no self-respecting citizen wanted to be seen entering the premises – day or night – even with hospital references. Jennings packed up and returned to Connecticut where he struggled to re-invent his practice in Hartford only to find more professional sabotage. Perhaps Jennings was naïve, with his nemesis only a few miles distant in Bristol. On November 25, 1929 -- a few weeks after the Stock Market crash, another tragedy struck the family when a newborn son, Joel Coolidge Jennings, died only three days after birth.

The Great Call North

By 1930, Jennings pulled up stakes in Connecticut to accept an offer from an old acquaintance (Dr. G.P. Gifford who had been impressed by his talk on rural hospital development ) and drove his family into the Green Mountains of Vermont – and the small town of Randolph. The town was nestled in the White River Valley with excellent rail connections to New York and Boston. More importantly for Jennings, Randolph had a clinic with forward-looking physicians who dreamed of expanding the facility to a hospital.. As a sweetener, the town offered Jennings a beautiful house with a wrap-around porch, a large barn, and adjoining office for his practice on one of its most prominent avenues, with close proximity to a nine-hole golf club.

A Country Doctor Flourishes

Vermont proved a “good elixir” for Dr. Jennings’ spirit. He employed his experience and leadership skills as a surgeon and a fundraiser/organizer to mount a successful campaign in partnership with Dr. G.P. Gifford and effectively modernized Randolph’s clinic into Gifford Memorial Hospital over the next twenty-five years. As the lead surgeon and a general practitioner, Jennings soon became the father figure for the next generation of physicians at Gifford. His love of the outdoors (camping, hunting, golf) was easily accessed in and around Randolph -- and Frank soon became a recognized leader in the community’s civic activities through Rotary Club, Bethany Church and Montague Golf Club. In 1931, at the age of 38, Nellie produced a third daughter, Naomi. Perhaps Frank had hoped for another son, but knew his wife could not risk another pregnancy.

As a respected town elder, Jennings wore his gruff, laconic exterior like a coat of armor, but his patients recognized the kindness and sincerity of his skilled care. He was sparing with words and worked to keep his volcanic temper in check. Often in the Depression the physician provided medical services with credit (extended repayment terms). He frequently saw patients at his home office where his wife kept the books.

Dr. Jennings married off his three daughters in his spacious, rolling backyard garden in Randolph, Vermont. All three had graduated from Randolph Union High School and gone on to become college graduates. His middle daughter, Marnie, graduated from Wellesley College with honors as a fiction writer in June 1941 and produced Jennings first grandchild -- a few weeks before the D-Day landings at Normandy in May 1944. The local newspaper recorded the proud grandfather’s joy, describing Jennings spontaneous rendition of “Rock-a-Bye Baby” sung at the Rotary Club meeting later that week (May 18) to announce the birth at Gifford. Jennings had assisted the birth. A second grandson was born to daughter Geraldine in April 1945. Both of his first sons-in-law were commissioned officers in the United States Navy on board ships when their sons were born. Dr. Jennings no doubt reminded them that he outranked them – having received a promotion to major in the Army medical reserves in 1924.

In the midst of his active life, Frank Jennings maintained contact with his Ivy League world by regularly attending Yale reunions and medical conferences. His familiarity with the patrician life-style of the wealthy and widespread contacts served him well when approaching potential donors for his various hospital and clinic expansion projects.

A Sudden End

Late in his career, Dr. Jennings branched out, spearheading the formation of the White River Valley Clinic at White River Junction in the 1950s. He made time to matriculate at the world renowned Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota -- learning the latest surgical techniques.

In early 1955, Jennings retired from the practice of medicine to spend more time on woodworking (he was an accomplished cabinet maker in his basement shop) and enjoyed his farm near Stockbridge.

Restless in retirement, he began traveling. Frank and Nellie had just returned from an arduous cross-country road trip to see the Grand Canyon in Arizona. On September 2, 1957, Dr. Francis Bates Jennings suffered a sudden heart attack and died at the hospital he had served, surrounded by colleagues and nurses he had trained who were unable to revive him. His unexpected passage shook Randolph. Grown men were seen crying in the streets. Several days later, Frank was laid to rest alongside his father and mother in the Jennings Family plot at Evergreen Cemetery in Brooklyn, New York. His sister, Ruth Hastings Jennings (Anderson) coordinated the funeral arrangements.

Sources:

History of Class of 1910, Yale University, New Haven, p. 200

Reports Regarding the Yale Mobile Unit in World War I, Dr. Joseph M. Flint, Yale University, 1920

“The Small Modern Hospital” Francis B. Jennings, (From Proceedings of Connecticut State Medical Society, 1926)

Daily Times (Barre, Vermont) “Dr. Gifford Takes Associate”. May 20, 1930

Randolph Herald, “Soloist” May 18, 1944

Randolph Herald, “Death Comes Suddenly to Two Randolph Neighbors”, September 5, 1957, p.1

Rutland Herald, “Dr. Jennings Dies at 71” September 3, 1957

Randolph Herald, “A Story- and a Tribute” Rev. Otis R. Heath (Summarized from remarks by officiating pastor at funeral of F.B. Jennings, Bethany Church, Randolph, Vermont – Sept. 5, 1957)

Randolph Herald, “From Randolph to Washington”, February 21, 2002 (Nicholas E. Hollis), p. B1

|

.jpg)