|

Old Pete at Liberty Place: Links to 1876 and Election 2000 by Nicholas E. Hollis The roller coaster ride of Election 2000 and its chaotic aftermath may be over, but the nation's jarred sensibilities, upset stomachs and exhausted disenchantment will take some time to adjust. Historians are reminding us of comparisons with the last electoral "train wreck" in 1876, another presidential struggle which dragged on too long. Samuel Tilden (D) had rolled up nearly 300,000 more popular votes than his Republican rival, Rutherford B. Hayes. But in the end, a "smoke-filled room" negotiation in Washington (Wormley Hotel) probably ratified Hayes after assurances were given for the removal of remaining Federal troops from three contested southern states -- Florida, Louisiana and South Carolina -- leading to the end of the Reconstruction Era.1 Critical Links to Liberty Place

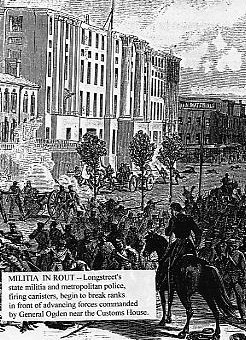

In some respects, the "Battle of Liberty Place" settled nothing. But the outraged members of the Knights of the White Camelia in New Orleans did make a point which probably figured heavily in the "deal of 1877." Reconstruction by Radical Republicans had been a disaster, and a new tragedy of missed opportunities for reconciliation was about to unfold. The seeds of wrath, which Abraham Lincoln had hoped to expunge with the nation's "better angels," were instead further nurtured into poisoned fruit by unchecked and somewhat vindictive excesses of the brutal Federal occupation and democracy itself! It took over eighty years for the New South to finally emerge and rejoin the Nation's prosperity. Even today, there remain great pockets of poverty and key sectors of our agricultural/rural economy which are ignored in a virtual "bayou of economic despair." The spiral of lower commodity prices and growing, fear-driven concentrations in the ag sector, are crushing what remains of the independent American farmer, grinding the "culture" out of agriculture. Our Nation's wound's barely healed after the Civil War and the rancorous Reconstruction which culminated with the infamous Tilden/Hayes struggle. But the "Battle of Liberty Place" was a pivotal event, rippling across the country's political and social landscape, leading to major Democratic gains at the polls in 1874, and signaling the beginning of the end of Reconstruction. When Longstreet rode out on Canal Street that balmy September afternoon to rally his troops, he demonstrated anew his resolute courage of conviction, his devotion to duty, and his unusual prescience. It also showed Old Pete's near-complete disregard for his own personal safety. Was he a traitor? or a true son of the South? Six years earlier Longstreet's proposals for peaceful reconciliation and black suffrage issues had been rejected, and now it was time to "pay the piper." Consistent with his belief that reunification and compromise were needed to preserve the South from further oppression -- and possibly vital to salvaging the best elements of southern culture, Longstreet's vision was decades ahead of his time. Yet, he was vilified and ridiculed -- his ideas ignored.

"No Guts, No Glory:" 1876 in

Perspective As we struggle to analyze our current political predicament for reconciliation themes -- and perhaps necessary reform, some historical consultation might be reassuring, even remedial. We have the opportunity to make some corrective choices. But any comparison with 1876 lacks "traction" today without a reference tot he Battle of Liberty Place. What happened there, painful as it is to recount, was more than a footnote in our history. After all, the 1874 clash reflects a struggle which continues to this day, barely under the surface, and it spells a warning for present-day policymakers: there is a price for disenfranchisement and close elections in a democracy. We will need to be industrious, honest, and vigilant in pursuing inclusive ways to strengthen our Nation in the wake of Election 2000. But, if we listen to "Old Pete," we can be stronger for it. ____________________ Further Suggested Readings: William A. Dunning, Reconstruction, Political and Economic, 1865-1877, New York: Harper Brothers, 1907, pp. 338-341. Judith K. Schafer, "The Battle of Liberty Place: A Matter of Historical Perception," Cultural Vistas, Vol. 5, No. 1 (Spring 1994), pp. 9-17. Robert G. Kaiser, "1876's Parallels Hold No Comfort," The Washington Post (December 17, 2000), pp. 34-35. N.R. Kleinfield, "President Tilden? No, but Almost, in Another Vote that Dragged On," The New York Times (November 12, 2000). "A Disputed Election's End Was Only the Beginning," The New York Times (November 19, 2000). |

|||||