The Search for Longstreet’s Honor: The Power of Nostalgia

Nicholas E. Hollis

All Rights Reserved

|

Twenty years have passed since Ken Burns’ award-winning Civil War series stirred American spirits, sparking a resurgence of historical inquiry and nostalgia unmatched since the 1890s when the first generation of veterans began to fade into eternity. Historical societies and roundtable forums flourished with renewed vigor while historians generated a flood of books and articles on virtually every aspect and personality linked to the War between the States. In the final episode of the Burns series the last reunions at Gettysburg on the fiftieth (1913) and seventy-fifth (1938) anniversaries of the epic battle, aging warriors in blue and grey clasped each other affectionately as comrades-in-arms and pledged allegiance to the tenants of reconciliation and peace. More than 150,000 participants, including some 1,800 actual veterans of the war, attended in 1938 and heard President Franklin D. Roosevelt dedicate the Eternal Light Peace Memorial.

Origins of Longstreet Memorial In the vast throng a group of former confederates -- led by the widow of CSA General James Longstreet (Helen Dortch Longstreet), Julius Franklin Howell, commander of the United Confederate Veterans (UCV) and others -- resolved to create an association to memorialize Longstreet and erect a statue in his memory on the battlefield. This was no small undertaking, especially for Helen Longstreet, who had campaigned tirelessly to rehabilitate and defend her husband’s reputation since his death in 1904. As a consequence of unrelenting attacks, distortions and degradation of his military record and character – linked with virulent adherents of the Lost Cause – no statues existed of Lee’s "Old War Horse" on any Civil War battlefield – North or South. Generations of historians, relying on published falsehoods fanned from the early 1870s after Lee’s death, had heaped enormous abuse on Longstreet’s record which had hardened with time. Helen Longstreet, an exceptionally gifted organizer -- as Georgia’s first female state archivist -- and a talented writer, was a natural leader and well suited to the challenge. At the helm of the new campaign – called the Longstreet Memorial Association (LMA) – Helen enlisted a Harvard educated history professor and Virginia college president, Julius Howell, who had also served in the Army of Northern Virginia under General Ewell in Company K of the 24th VA Cavalry primarily in the defense of Richmond. Howell had been wounded and captured at Sailor’s Creek a few days before the War ended in April 1865. Later in life, he became state commander of Tennessee Confederate Veterans before rising to the national organization (UCV) leadership.

Nostalgia as a Mobilizing Force After several years of organizational efforts and correspondence, just as the fundraising for the statue was poised for launch -- following a dramatic groundbreaking ceremony at Gettysburg in July 1941 -- the LMA was forced to suspend its campaign with the U.S. entrance into World War II. Helen had been meticulous in organizing the Gettysburg ceremony. She had traveled the country, giving talks, staging exhibits and publishing articles. Throughout her campaigns, Helen enlisted supporters and sympathizers. She had also commissioned a renowned sculptor, Paul Manship, to design an impressive scale model of a Longstreet equestrian statue and negotiated the approvals and selection of a plot for its eventual full-sized placement on the battlefield with the National Park Service (NPS).

As Helen developed her national network for LMA, she admonished her regional coordinators to avoid any hint or appearance of commercialization which could give enemies of the campaign an opening to impugn its motives and "attack Longstreet’s memory anew" (February 21, 1948 Letter to Carl N. Breihan of Affton, Missouri). The warning would echo decades later (and be ignored) in latter-day Longstreet tributes. After the war, Helen, now in her mid-eighties, pinned her dwindling hopes for a resurgent organizational effort around Julius Howell and preparations for another Gettysburg reunion (85th) in July 1948. As president of the LMA, Howell had gained considerable prominence in the intervening years. He had been featured in Life Magazine (1942) as one of the longest-lived Confederate veterans, and addressed Congress on the eve of the Normandy Invasion in June 1944. Helen also maintained the support of Hollywood celebrity Mary Pickford, who held center stage at the statue dedication and recognized the power of nostalgia, symbolized in the aftermath of Gone with the Wind (1939). Unfortunately, after considerable celebrity fanfare greeted Howell’s 102nd birthday, including a New York Times feature in January 1948, the venerable Confederate fell ill and passed away peacefully in Bristol, Virginia on June 21 – only ten days before the planned program at Gettysburg.

A House Divided Other forces were busy mining the Longstreet legacy entwined with national fascination surrounding American warriors -- and some were quite damaging to the General’s reputation. The worst was House Divided, a novel by Ben Ames Williams, who had used his family links (Williams was a grandson of one of Longstreet’s sisters, Sarah) to approach the General’s son, Fitz-Randolph Longstreet and others, including Helen, ostensibly to gather insights into Old Pete’s personal side. Released in 1947, the novel became a best seller. However, instead of defending General’s military honor, Williams relied on Longstreet critics in developing the novel’s main character- and depicted the General as willful, insubordinate and wracked with doubts about his loyalty to Lee. Williams hit a another low with his portrayal of Longstreet in The Unconquered (1953), a sequel to House Divided, which was also highly critical of the General. Sadly, the perverse temptation to utilize Longstreet’s fame while betraying trust, including siding with known detractors for gain, continues into the present. Despite a revival of interest in the Civil War during the 1950s leading into the centennial years of the sixties, momentum for Helen Longstreet’s statue campaign never recovered. She died heartbroken and alone in 1962 in a Georgia sanitarium. Another thirty six years slipped away before a group of North Carolina’s Sons of Confederate Veterans erected an tribute statue depicting a mounted Longstreet at Gettysburg (Sculptor- Gary Casteel) –the culmination of an intense seven year campaign in 1998.

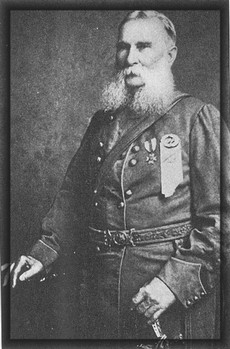

LONGSTREET IN OLD AGE "Old Pete" attended numerous veteran reunions where he praised former classmates and comrades from the Mexican War and the Cilvil War, including U.S. Grant.

Conclusion As a veteran of numerous reunions and anniversary celebrations after the Civil War, Longstreet knew the power of nostalgia. Although his voice was impaired due to his neck wound at Wilderness, Old Pete was always a favorite speaker. His message of reconciliation drew large audiences and approval, especially in the North. The General understood the symbolism of an old warrior facing the future with confidence. We could learn from Old Pete and be stronger for it.

Nicholas E. Hollis General Longstreet Recognition Project (GLRP) P.O. Box 5565 Washington DC 20016

|

||||||||

|

Additional Sources Piston, William Garrett. Lee's Tarnished Lieutenant: James Longstreet and His Place in Southern History (1987) Gettysburg Times, July 2-3, 1941 New York Times, July 2, 1913 Atlanta Constitution, July 4, 1938 Longstreet Memorial Association, "The Great American" Pamphlet (1941) |